"The Odd Couple": The Unlikely Friendship of Joe Biden and Strom Thurmond

What America forgot but Joe can't.

At a recent fundraiser, President Biden sparked controversy with a nostalgic comment about deceased South Carolina Republican Senator Strom Thurmond.

I've been a senator since '72. I've served with real racists. I've served with Strom Thurmond. I've served with all these guys that have set terrible records on race. But guess what? These guys [the GOP Congress] are worse. These guys do not believe in basic democratic principles.1

While Biden attempted to qualify his comment, acknowledging that Thurmond “did terrible things,” he emphasized that, “at least you could work with some of these guys.”

Many Democrats found Biden’s remarks alarming. Did he really mean that he would rather work with Strom Thurmond — the man who in 1948 said, “[T]here’s not enough troops in the Army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Negro race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches”; who broke (and still holds) the record for the longest filibuster in Senate history opposing the Civil Rights Act of 1957 — than the current crop of Republicans?2 In a word: yes. Why? Because, to Biden, Thurmond was more than a colleague; he was a friend.

When Biden first entered the Senate in 1973, he had no intention of befriending the septuagenarian good ol’ boy and one-time “hope of the South.” In fact, Biden would later remark that, “the reason I got into politics was to fight the Strom Thurmonds.”3 As he recalls, he was outraged at the horrific mistreatment of African-Americans in the United States, which, “for a period in his life, Strom had represented.”4 He was prepared to find an enemy in Thurmond. “[B]ut then I met the man,” he said, and everything changed. Biden didn’t know how or why, but he and Thurmond began to become friends, and as they did it became easier for him to overlook his politics. “Our differences were profound,” Biden reflected, “but I came to understand that, as Archibald MacLeish wrote: ‘It is not in the world of ideas that life is lived: Life is lived for better or worse in life.’”

Despite what Biden saw as profound differences between himself and Thurmond, they quickly found common ground on a divisive civil rights issue: busing. By the ‘70s, conservatives like Thurmond who once freely identified as segregationists had been forced to adjust their rhetoric in order to maintain political viability. Instead of attacking desegregation directly, they began to target the implementation of desegregation, specifically busing — or, as they called it, “forced busing” — which was growing increasingly unpopular.5 Lee Atwater, GOP strategist and Thurmond protege, outlined this shift in an (unpublished) 1981 interview:

You start out in 1954 by saying, “N*gger, n*gger, n*gger.” By 1968 you can’t say “n*gger”—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract.6

Wittingly or unwittingly, Biden, who was feeling the heat from his constituents, adopted this same coded language and took up the cause against busing.7 In 1975 he wrote a bill — co-sponsored by Thurmond — to “prohibit HEW [the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare] from assigning teachers or students to schools for reason of race.”8 As Biden later acknowledged, he normalized liberal opposition to busing.

“I think what I’ve done inadvertently ... is, I’ve made it—if not respectable—I’ve made it reasonable for long standing liberals to begin to raise the questions [about busing] I’ve been the first to raise in the liberal community here on the floor.”9

By normalizing this reactionary position among liberals, Biden helped to blur partisan lines and give conservatives political cover.10 Thurmond didn’t have to moderate his position to rejoin the mainstream, Biden brought the mainstream to him.

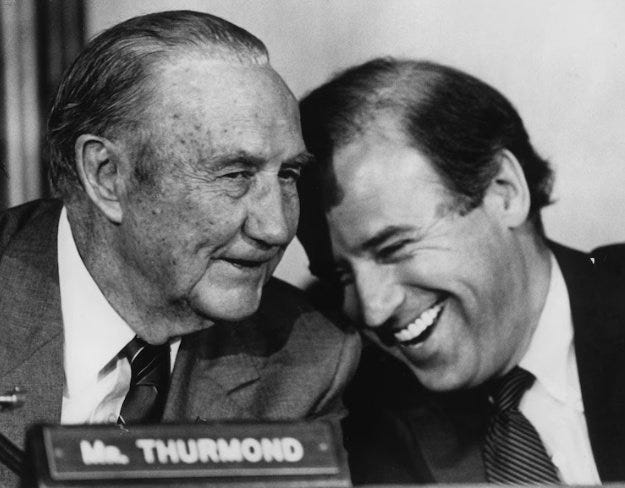

In the ‘80s, Biden and Thurmond became something of a dynamic duo. In 1981, Biden became the ranking minority member of the Senate Judiciary Committee which Thurmond chaired until 1987 when Biden took up the mantle himself. Despite representing opposite parties, they found their views on criminal justice largely compatible. When Biden met with Thurmond to hash out the 1984 Crime Bill — which he called “the most significant reshaping of criminal legislation in the last 30 years” — he found that they agreed on as much as 95% of its provisions and were able to take the remaining 5% and “put it on the shelf” in order to reach a bipartisan compromise.11 Together they co-authored a number of tough-on-crime bills — including the (failed) Biden-Thurmond Violent Crime Act of 1991, the precursor to Biden’s infamous 1994 Crime Bill — which transformed the country’s criminal justice laws.12

During this period, Biden and Thurmond developed a bond of mutual loyalty. According to Jack Bass and Marylin Thompson’s biography of Thurmond,

[…] Biden as ranking Democrat [on the Senate Judiciary Committee] had forged a good relationship with Thurmond by promising never to do anything to uncut him. Thurmond reciprocated.13

This loyalty proved strong enough to withstand even the fiercest political shitstorms.

In 1987, when a series of plagiarism allegations sank Biden’s presidential campaign and called his political future into question, Thurmond had his back.14 As Biden recalls, when he delivered an apologetic speech to the Senate Judiciary Committee, offering to step down as Chairman, Thurmond sprang to his feet. “You’re my Chairman,” he declared.15 With that, everyone else stood in agreement. “He did not seek a single explanation for what I had been accused of,” said Biden. “Clearly, when partisanship was a winning option, he chose friendship.” Thurmond had thrown him a life raft, and he would do his damndest to return the favor.

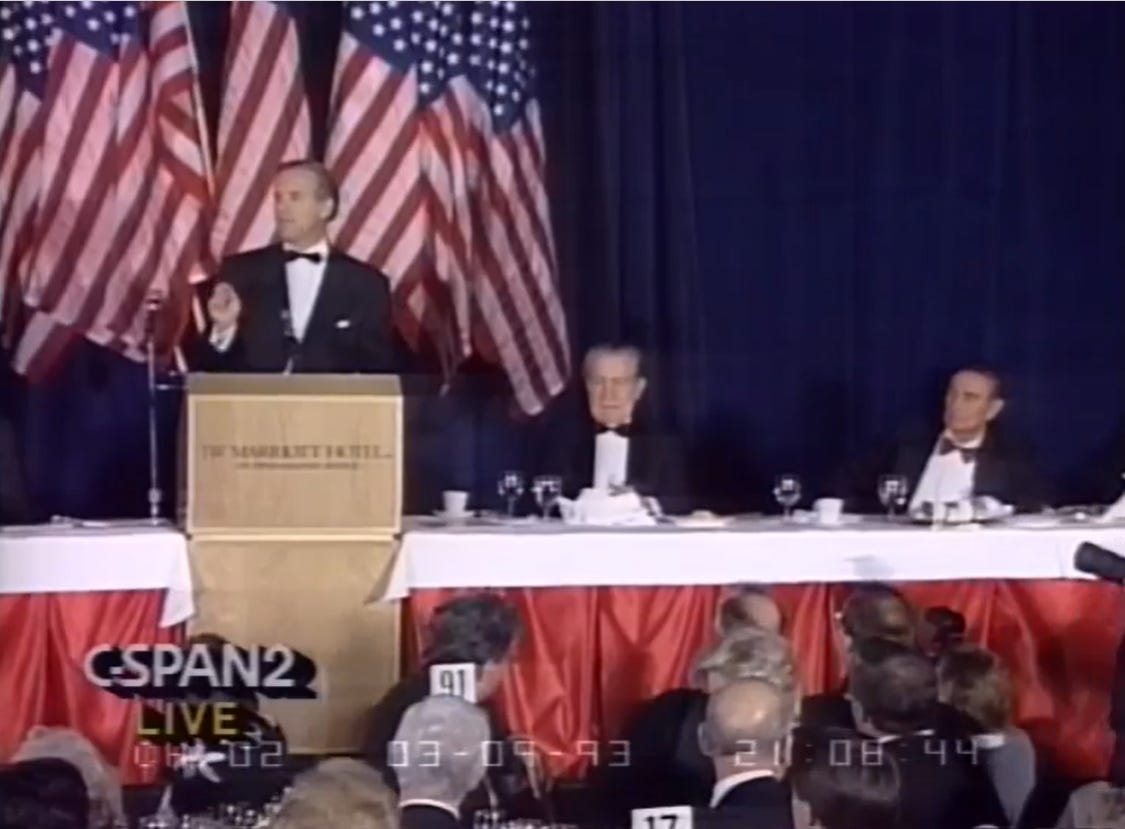

By the ‘90s, Biden and Thurmond’s unlikely friendship had become a well known institution on the hill. Some colleagues even affectionately called them “the odd couple” and subjected them to an occasional ribbing. At Thurmond’s 90th birthday celebration in 1993, Senator Bob Dole joked,

[T]hroughout the last decade, [Thurmond’s] Democratic counterpart on [the Senate Judiciary] committee has been Joe Biden. This friendship has surprised some. After all, Joe’s young enough to be Strom’s son. Come to think of it, who isn't young enough to be Strom's son?16

At the same event, Biden lionized Thurmond — comparing him favorably to Winston Churchill, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson — and said of their curious friendship,

Little did anyone think, including me, when I had an opportunity to be ranking member [on the Senate Judiciary committee] with Strom, that I would grow to have such genuine and deep affection for him.17

After toasting Thurmond, he continued to sing his praises, asserting that he was without equal:

[…] I know of no man with whom I’ve served — or woman — who has as star-studded a past and as promising a future, and looks to the future all the time, as you do.

In 1997, when Thurmond broke the record for longest-serving Senator, Biden delivered yet another heartfelt tribute, saying,

[Thurmond’s] political longevity lies […] deep within Strom Thurmond himself. It lies in his strength of character, his absolute honesty and integrity, his strong sense of fairness, and his commitment to public service. None of those things are skills which you learn; they are qualities deep within you which, when people know you well, they can sense. That is the secret to Strom Thurmond’s success.18

Time and again, Biden served as Thurmond’s personal hagiographer, and the aging Senator took notice.

In 2003, Thurmond, now 100-years-old, fell ill. Just before his death, Thurmond’s wife, Nancy, called Biden to inform him that he was now “on God’s time” and had one last request: for him to deliver a eulogy. Biden said this request, “flattered me greatly and saddened me significantly.” The week before the funeral, Biden spoke to the Senate at length about his friend, addressing some of the more sordid chapters in his history, specifically his record on race:

I do not believe that Strom Thurmond, at his core, was a racist. But even if he had been, I believe he changed.19

His evidence for this claim was that Thurmond had a higher percentage of African-American staff members than anyone else in the Senate and voted to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act — points he has repeated over the years, notably during his 2009 Senate farewell address and again at the fundraiser last month.20

When Biden delivered Thurmond’s eulogy, he continued to highlight how the man had changed, not just outwardly to keep with the times, but in his heart:

This is a man who I watched vote for the extension of the Voting Rights Act. This is a man who I watched vote for the Martin Luther King holiday. And it’s really easy to say today that that was pure political expediency, but I choose to believe otherwise. I choose to believe that Strom Thurmond was doing what few do once they pass the age of 50: he was continuing to grow, continuing to change.21

With this, Biden wrote Thurmond — the good ol’ boy, the segregationist — a more favorable legacy. He wasn’t a racist; he was a man of his times, and one who was willing to change. Now, is that really true? Did Thurmond change in his heart of hearts? Probably not — he never apologized for his past and didn’t seem to believe he’d done anything wrong.22 But that isn’t important. What’s important is that Biden believed it.

To Biden, his friendship with Thurmond is emblematic of a bygone era of civility and bipartisan compromise, where two men could set aside or, better yet, learn from each other's differences and become friends. But in reality, he and Thurmond were less different than he would like to admit. And when push came to shove, they valued loyalty over principle. Their friendship was one of mutual benefit, allowing Thurmond to reinvent himself and Biden to embed himself in the establishment. Though at first blush, they seem like an unlikely pair, a closer inspection reveals the truth: they were perfect for each other.

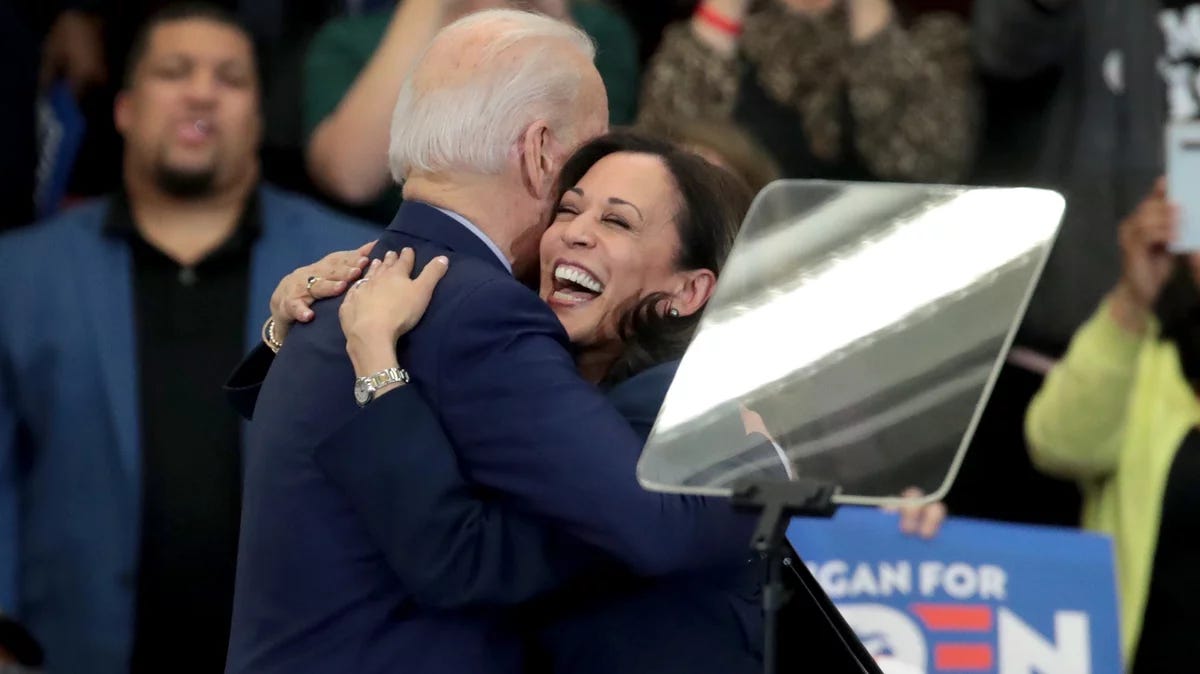

Now Biden is in the same position he found Thurmond in in 1973. He’s the aging politician with the checkered record, prone to rambling about long-dead friends and colleagues, once fiery but now cranky and doddering. And he too has had to adjust his rhetoric to changing times. During one of the Democratic Primary debates in 2019, then-Senator Kamala Harris took a shot at Biden over his warm comments about segregationists — in this instance, Senators Jim Eastland and John Stennis.23 This generated an enormous amount of negative press. But Biden took a play from Thurmond’s playbook: he made his enemy not just an ally, but a partner.

It’s clear that Biden picked up a thing or two from Thurmond, but why does he continue to mention him by name even now that it’s no longer politically expedient to do so? Maybe politics has nothing to do with it. Maybe it’s sentimentality. Perhaps Biden still remembers his friend fondly, like he did when he said farewell in 2003:

[…] I knew Strom well. I felt his warmth as you did. I saw his strength, as you did. I was a beneficiary of his virtues, as you were. And I’ll miss him, as you will. As we all will.”24

Epstein, Reid J. “Biden Calls Republicans in Congress ‘worse’ than Strom Thurmond.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 22 Feb. 2024, www.nytimes.com/2024/02/22/us/politics/biden-strom-thurmond-republicans.html.

Merida, Kevin. “The Seniority of Strom Thurmond.” The Washington Post, 25 Apr. 2001, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2001/04/26/the-seniority-of-strom-thurmond/b0e1ed9d-f150-4261-b7c5-ed1f57dd1e06/.

Merida, Kevin. “The Seniority of Strom Thurmond.”

Biden, Joseph R. “Joe Biden Eulogy for Strom Thurmond.” C-SPAN.org, 1 July 2003, www.c-span.org/video/?c4790947%2Fjoe-biden-eulogy.

Crespino, Joseph. Strom Thurmond’s America. Hill and Wang, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013, 256-257.

Perlstein, Rick. “Exclusive: Lee Atwater’s Infamous 1981 Interview on the Southern Strategy.” The Nation, 13 Nov. 2012, www.thenation.com/article/archive/exclusive-lee-atwaters-infamous-1981-interview-southern-strategy/.

Ross, Janell. “Joe Biden Didn’t Just Compromise with Segregationists. He Fought for Their Cause in Schools, Experts Say.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 25 June 2019, www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/joe-biden-didn-t-just-compromise-segregationists-he-fought-their-n1021626.

Crespino, Joseph. 257.

Gadsden, Brett. “Here’s How Deep Biden’s Busing Problem Runs - Politico Magazine.” Politico.Com, 5 May 2019, www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/05/05/joe-biden-busing-problem-226791/.

Crespino, Joseph. 258.

Biden, Joseph R. “User Clip: Biden & Strom Thurmond on Drug Laws.” C-Span.org, 26 Sept. 1986, www.c-span.org/video/?c4800808%2Fuser-clip-biden-strom-thurmond-drug-laws.

Stolberg, Sheryl Gay, and Astead W. Herndon. “‘Lock the S.O.B.S up’: Joe Biden and the Era of Mass Incarceration.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 June 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/06/25/us/joe-biden-crime-laws.html.

Bass, Jack, and Marilyn W. Thompson. Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond. 2005, 299.

Satija, Neena. “Echoes of Biden’s 1987 Plagiarism Scandal Continue to Reverberate ...” The Washington Post, 5 June 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/echoes-of-bidens-1987-plagiarism-scandal-continue-to-reverberate/2019/06/05/dbaf3716-7292-11e9-9eb4-0828f5389013_story.html.

Biden, Joseph R. “Joe Biden Eulogy for Strom Thurmond.”

Dole, Robert. “Strom Thurmond 90th Birthday Dinner.” C, 9 Mar. 1993, www.c-span.org/video/?38599-1%2Fstrom-thurmond-90th-birthday-dinner.

Dole, Robert. “Strom Thurmond 90th Birthday Dinner.” C, 9 Mar. 1993, www.c-span.org/video/?38599-1%2Fstrom-thurmond-90th-birthday-dinner.

Biden, Joseph R. “Strom Thurmond 90th Birthday Dinner.” C, 9 Mar. 1993, www.c-span.org/video/?38599-1%2Fstrom-thurmond-90th-birthday-dinner.

Bass, Jack, and Marilyn W. Thompson. 299.

Biden, Joseph R. “Biden Tribute Thurmond.” C-Span.org, 27 June 2003, www.c-span.org/video/?c4996472%2Fbiden-tribute-thurmond.

Biden, Joseph R. “Senator Biden Farewell Address.” C-Span.org, 15 Jan. 2009, www.c-span.org/video/?283385-2%2Fsenator-biden-farewell-address.

Biden, Joseph R. “Joe Biden Eulogy for Strom Thurmond.”

Noah, Timothy. “The Legend of Strom’s Remorse.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 16 Dec. 2002, slate.com/news-and-politics/2002/12/the-legend-of-strom-s-remorse.html.

Collins, Michael, and John Fritze. “‘That Little Girl Is Me’: Kamala Harris Attacks Biden with Personal Story about Race.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 27 June 2019, www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2019/06/27/democratic-debate-2019-night-2-kamala-harris-attacks-biden-race/1591553001/.

Biden, Joseph R. “Joe Biden Eulogy for Strom Thurmond.”

Additional Sources:

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. “Was Strom a Rapist?” The Nation, 29 June 2015, www.thenation.com/article/archive/was-strom-rapist/.

Drehle, David Von. “Opinion | What Biden’s Eulogy for Strom Thurmond Says about - The ...” The Washington Post, 27 Oct. 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/biden-will-need-partners-to-restore-our-institutions-where-will-he-find-them/2020/10/27/11f3f506-186d-11eb-befb-8864259bd2d8_story.html.

Perlstein, Rick. Nixonland: America’s Second Civil War and the Divisive Legacy of Richard Nixon, 1965-1972. Simon & Schuster, 2009.

Zelizer, Julian E. On Capitol Hill: The Struggle to Reform Congress and Its Consequences, 1948-2000. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006.

Great article, looking forward to seeing more